A few years ago (not sure but it was probably nearly two decades ago now) I was watching A Current Affair. I think Ray Martin was the host. The episode featured a story I will never forget. It was a news story from the United States, from a small town somewhere in the south. They showed lots of poorer neighbourhoods, lots of young men standing on the street 'loitering'. Also featured in the story was the town's mayor and local police chief. The story was about this new trend in many of the poorer areas of the town where groups of young men (mostly African American men) wearing their jeans so low that their underwear was visible. There were interviews with some of the young men, the town's leadership and the odd vox pop from locals who were disgusted with this new trend. The township were up in arms and were trying to determine if any in/decency laws could be used to stop the tide of this unsocial and uncivilised behaviour. At the end of the piece, Ray shook his head in disgust.

I remember this story for two reasons. The first reason was because I

was bemused at this new trend thinking 'well that won't last long, just

leave the kids alone and they'll pull up their pants'. How wrong was I?

But secondly, I was thinking, what the report didn't say and what was

invisible to the town's leadership was the disenfranchisement of significant

segments of that community. There's a now well known quote by a young

person from the British riots this month who, when asked by a report why

he was angry and why he was rioting, said, well you wouldn't be talking to me if I wasn't.

Perception

Let's look first at the idea of perception. For the purposes of this blog-post-lecture, I'd like you consider that perception is different from truth and different again from reality. When we perceive something, what we see is not the truth, but is in fact only what we perceive to be the truth.

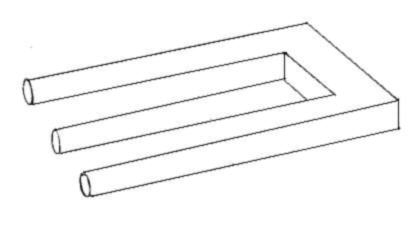

Have a look at the Escher image below:

Whatever your answer - you are not wrong. Another image below - are there two or three legs on this diagram?

Once again, you are not wrong, it just depends on your perception and your gaze.

Iceberg metaphor

Where does our perception, and for this discussion, our cultural perceptions come from? The cultural iceberg metaphor is used by a lot of cross-cultural educators around the world and is very useful for getting an understanding about the source of cultural perceptions.

Let's consider an iceberg for a moment.

How is an iceberg structured? An iceberg is typically structured with approximately 10% of it's mass above the water line, while 90% of it's mass is hidden below the surface. Thus the saying, the tip of the iceberg, really does reflect the reality of the iceberg. (Click here for an awesome image of an iceberg)

When we're looking at or are thinking about an iceberg - we know that the bulk of an iceberg (the really important stuff that gives the iceberg it's body) is hidden.

Okay, now let's take this picture/metaphor of an iceberg and think of it as culture - what can we see and what can't we see? It leads us to two very important questions:

1. What of culture is visible?

2. What of culture is invisible or hidden?

Why are these questions important?

Because if you don't know that there are visible and invisible aspects to culture, then you're more likely to fall into the trap of believing that all there is to culture is what you can see. And that view is really only just a superficial part of culture - all the good stuff, the meaningful stuff of culture is underneath, it's hidden. But that hidden stuff is just as, if not more important than the stuff we can see.

So what can we see? On the iceberg below - what are the things that you can see and can't see of culture?

Click here to contribute to a Google Doc about the visible & invisible aspects of culture.

Question: Can you think of instances where you have dismissed or made

assumptions about another culture just because of what you saw?

Consider that culture isn't just about what we do (the stuff above the water line), but that it's much much deeper than that.

Culture is something that is learned. We are not born with it, but rather we accumulate information through our social interactions, which in turn we require to interact with each other in our social lives (Thornton 1988). It is two things in particular: that which we practice, and the reservoir of all that is known and thought (Said 1993). Culture is a shifting resource, cyclic in nature, which evolves through our social practices and because of the changing way that we think about it and ourselves (Mare 1993). Fundamentally then, culture is not just the things we do, but most significantly the values, attitudes and ideologies which underpin our decisions and choices in these respects. Because it is a lived experience, remade over as we make meaningful social exchanges, it cannot be separated into a neat compartment, devoid of human concern nor neatly severed from history. We are defined by our experiences of history, and our past is embodied in the ways in which we deal with each other now; for individuals as well as culture collectives. Phillips (2006)

Question: Try to describe your culture. How do you know what you know about who you are culturally and socially? [consider not only culture & race, but also gender, sexuality, generation, parenting, language etc]

When I think about culture and about what is generally thought to be 'cultural', I tend to get a little bit annoyed at how the superficiality (or the decoration) of culture is given more credibility than what is deeper. In fact, superficial definitions of culture are often used by public commentators in Australia as a way of dismissing modern and contemporary Indigenous identity. Many commentators argue that because a lot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people no longer ' live in the bush', have dark skin, and a whole range of other visible aspects of culture, then we are not 'real'.

I think the two images below illustrate different perceptions of a reality (the reality in this case is the actual continent) - but there are two different ways of seeing that reality.

The map on the left is a map of Australia with the states & territories marked out. Of course, this map is true. It's official and is the map that we as Australians live by today. The map on the right is the Map of Aboriginal Australia produced by Dr David Horton and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in 1994. Is this map true? This question may be answered in a number of ways. Some will say it was true before 1788, while others may say yes, it's true but it doesn't mean anything in reality because we're all Australians now, and no it's not true, it doesn't mean anything. Regardless of your answer, the point is, the two maps of the continent show very different perceptions of reality, they show different truths.

Western and Indigenous Knowledge

Let's look now at some of the key characteristics in Western and Indigenous cultures. Below are some of the characteristics of both.

Question: Where can you see these characteristics in real life? Do they apply to you? How do they differ?

Impact of this on your professional practice

I alluded above to the issue of power. Looking at the two maps of

Australia - it is power which dictates that one map is official and

another is un-official. If you have not seen the second map before this

lecture, consider that once again it is power that has determined this. (Moreton-Robinson 2000)Impact of this on your professional practice

Phillips (2006) asserts that what is acceptable historically (as part of the dominant culture) has a number of sides to the story.

This connected sense of collective belonging is sustained by the links we maintain with our forebears and the reproduction of their stories, consciously and unconsciously, in schools, the media and other social - and socialising - spaces. If the basis for the knowledge we hold about ourselves and our relationships to others is circulating through the same historical events, then how we think about or know ourselves in the present is subject to their actual and ideological influence. The pioneering spirit of early British settlers and the commonly held belief in Australian egalitarianism are symbolically remembered and reproduced in many ways to fortify collective beliefs about the meaning of 'our' culture as Australians. Just as this popularly expressed Australian ethos of a 'fair-go-for-all' has evolved from events in the great 'pioneering', Indigenous peoples' experience of these same events has led to our marginalised position, for such pioneering required our 'dispersal' to the fringes. The refusal to regard the 'other side of the frontier' (Reynolds 1990) as pertinent to collective Australian culture today is, as Colishaw (1999, pp.9) eloquently puts it, the inability to accept that 'there were other imaginations, other meanings and other lives being lived out in the domain the colonisers always though of as theirs'.Thus in relation to your professional practice, what role will you take in ensuring different perceptions, understandings, knowledeges and imaginations are considered? Consider the forces that have shaped and framed how you see and read the world? How do they impact upon your ability to analyse the world around you?

In ways are you shaped and framed by your culture, gender, race, age, etc?